|

||

|

||

| ||

Part 5: Brief Introduction into AVIVO and Bottom Line

TABLE OF CONTENTS

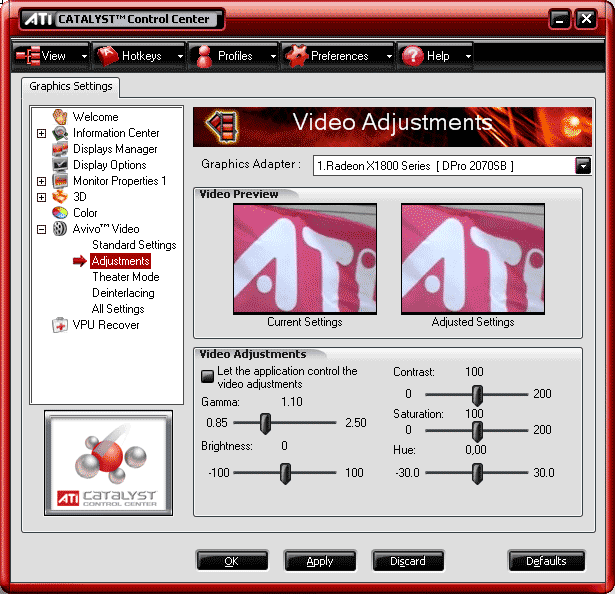

Brief introduction into AVIVOEar-caressing term "VIVO" will probably put our readers on to the old all-purpose VideoIn and VideoOut. And the first letter A in the term will be read as Advanced, that is something better. And they will be right in a way. But still, AVIVO is a huge complex of video processing capacities (except for 3D). AVIVO is intended to improve the end-to-end pipeline of a video stream until it is displayed. It's a whole complex. The video pipeline consists of the following stages:

AVIVO: Digital CaptureIn the new products, it will be the responsibility of an advanced ATI Theater 550 processor, which will be installed either on separate boards (to be used together with the main video card) or on All-in-Wonder media centers. It uses 12-bit analog-to-digital converters.

AVIVO: EncodeThis part will be taken by VPU (GPU) itself. Of course, we mean only the new X1000 series, only these processors can encode the following formats on the hardware level: H.264 (new!), VC-1, WMV9, WMV9PMC, MPEG-2, MPEG-4, DivX. Of course, there will be an option to transcode the above listed formats. All of it will be available in the nearest future, after the new drivers are released (plus proper software). The H.264 format is of little use to Russian users so far. But software video encoding in this format takes up terribly much CPU resources.

AVIVO: DecodeThe reverse process works absolutely the same, of course, on the hardware level. Up to now, GPU has taken part only in MPEG-2 decoding. And now all formats will be decoded on the hardware level. The biggest effect from such buck-passing to GPU will be in case of H.264 (not quite relevant for the majority of Russian people). But it's very important for promoting new HD-DVD and Blu-ray technologies, as CPU requirements for their software decoding exceed DVD (MPEG-2) decoding as 8-10 to one. All this will be delegated to GPU! This is evidently done reckoning future prospects! By the way, NVIDIA promises a similar technology a tad later, by the end of the year.

AVIVO: Post ProcessingBefore displaying an image, it should be processed (so-called post processing in 3D). We know that deinterlacing is included into the list of such functions. AVIVO offers a new type of vector deinterlacing. It's an immediate competitor to a similar technology, offered by NVIDIA in PureVideo.

Our author Alexei Samsonov has taken upon himself to review AVIVO and PureVideo. So we look forward to his article full of details on pros and cons of each technology, taking into account what and how has been already implemented. GENERAL CONCLUSIONSA short digressionOn the one hand, the architecture is innovative. On the other hand, it's controversial. There is a feeling of something incomplete — of an intermediate milestone. As if the R520 is not a stand-alone product, but just a stop on the way to the bright WGF 2.0 future represented by the R600, or what you may call it. Not just a stop, but only half of the platform. The second half is Xenos — Xbox 360 graphics chip. Merged together, plus what is just asking to be added, here is the joy. One the one hand, we've got a cool scheduler, which solves the principal problem of efficient shader execution with branching. On the other hand, why aren't shader processors unified? Such architecture would not have needed practically any additional changes, if kept to minimum and not modifying the entire concept. But no, shader processors in xenos are unified already, unlike these products. Or another example - floating point format of the frame buffer — it supports both blending and MSAA. But there is still no filtering for such textures. So almost everything works in FP16 mode, except for the most important — filtering fetched textures. Why implement MSAA in this mode and not bring the concept to an end? Or take vertex processors — there is no vertex texture fetch. It's a pity. It should be noted that pixel shaders with rendering into a vertex buffer are recommended instead. It also solves the problem with no texture filtering. The number of pixel pipelines is smaller than recommended for absolute leadership. The number of texture units in the RV530 is an obvious weak spot, a bottleneck. This list can be expanded with petty issues, but the result is the same — a strong feeling of an intermediate solution. We look forward to the optimized R580, hopefully with more pipelines; we look forward to the R600, which will hopefully not only take the best features from Xenos and R520, but also add everything these accelerators need. As for now, we have a wonderful new "spin", with a new architecture, expectedly "spoiled". The architecture is promising, but not without drawbacks. The drawbacks are not too strong to speak of R5x failure. But the capacities are not that revolutional to speak of its superiority over competitors. ATI has caught up with NVIDIA, having established a promising architectural base. But this base is for the future, for WGF 2.0 and the R600. Should you buy the R520 or you'd better wait for the R580? That's the burning question for ATI fans, as the overhauled solution promises to reveal more of the potential of the new architecture. We'll see! As for now, having examined the R520 and Xenos like two halves of a banknote, we can imagine what we can get from the R600 — WGF 2.0 oriented architecture Test Conclusions

So what have we got as a result? The new cards confidently catch up with their competitors from NVIDIA, sometimes even take up the lead, though they still fall behind in some cases. If we ignore performance variations and equate the X1800XT with the 7800GTX, we shouldn't forget about the objective advantages of the entire X1000 series, such as new AA and AF types, AVIVO, DualLink DVI, etc. However, there is a real danger of the X1800XT hitting the shelves significantly higher than $500, there will be a wide price gap from the 7800GTX. The products possess a number of wonderful and necessary features, but they failed to make the so-called break-through, that is to radically outrun the competitor. The reason is simple - they are late. Besides, only few of the new cards have hit the shelves now, the rest will come later. Each delayed day on the eve of Christmas sales brings losses 10 or even 20 times as high as in any other season. I hope the Canadian company is aware of that. The company has already lost 100 million dollars to blunders made by some departments last quarter. I just hope that there will be much fewer mistakes in future. But we should admit that the innovations in the R520 are worthy of respect. First of all, the principally new memory controller scheme, Ultra-Thread technology, etc. The current generation is doomed (sooner or later we shall come to unified shaders), considering Microsoft Vista with DirectX10 to be released in a year, which will need new hardware). It seems why waste efforts now, they still have to produce new products in a year, equipped with principally new 3D technologies. But we should take into account that lots of games are coming out, which use the latest innovations in DX9.0c. Gamers will play them now, not in a year. If you consider video performance in F.E.A.R., for example, you will understand that the speed is not too high in absolute figures in the maximum quality mode (this moral right has been earned by people, who spent $500 for an accelerator). Besides, many gourmets will appreciate improved quality (performance-affordable AA 6x, improved anisotropy). And don't forget about the future R580 from ATI: the new features from the R520 may shine there, even if they are ineffective now. But we shall keep tabs on the new series already among production-line cards. Besides, new drivers for these cards should be released soon. Stay with us and wait for further analysis (there are still many issues to review: ineffective HDR, the lack of overclocking potential, etc. Plus the article on AVIVO from A.Samsonov ).  Write a comment below. No registration needed!

|

Platform · Video · Multimedia · Mobile · Other || About us & Privacy policy · Twitter · Facebook Copyright © Byrds Research & Publishing, Ltd., 1997–2011. All rights reserved. |