|

||

|

||

| ||

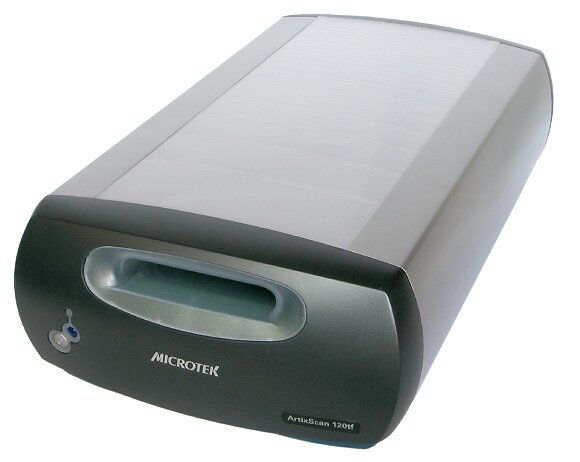

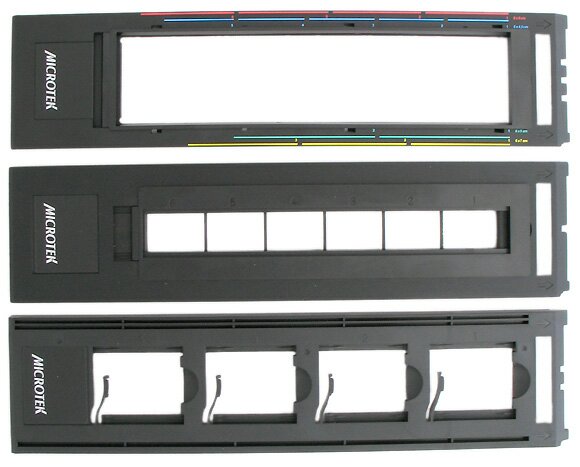

Universal film scanner for 35mm and 60mm films supporting up to 4000 dpi The specs of the ArtixScan 120tf scanner can be found on Microtek's site. We are going to tell you about its features we have examined. Scanners of this class have so many degrees of freedom that it can take months to find optimal methods to handle them. The scanner looks interesting because there are few models of this class on our local market. Actually they are Minolta Dimage Scan Multi Pro which was earlier reviewed and Nikon SUPER COOLSCAN 8000 ED which we couldn't get yet. Both scanners, i.e. the tested one and the Minolta, were connected to the same PC and scanned the same negative. 4000 dpi is more than enough and the scanner can get more out of some films; nevertheless, its capabilities are excessive for most photographic tasks. That is why we had an opportunity to range cameras of the last seventy years. The comparison looks quite logical. First of all, we don't get that excessiveness we have with print scanning. A print looks finished and it doesn't need any scanning. Negatives scanning simply replaces printing under a magnifier, and it's getting more popular - many photo labs first scan negatives and then print digital photos. This scanner makes a photographer almost independent. If it's really a big problem to arrange color printing at home, it won't cost you much to develop films on C-41 and E6, not to mention black-and-white films. I think that if photo labs begin to accept only digital storage units, it won't be a sign to replace your film camera with a digital one. Shots taken with a 50 years old camera can look much better because even top-notch auto cameras will never substitute photographer's experience. So, here's our hero. The scanner can be connected to PC via SCSI or IEEE 1394 interface.  The scanner is bigger than the Minolta Dimage Scan Multi Pro and it supports packet scanning and scanning of wide films. At a time you can scan 6 35mm frames or 2 6x9, 3 6x7, 4 6x6 or 5 4.5x6cm frames. It also allows scanning framed slides, though the manufacturers do not consider it a useful feature because holders for films are metallic and this one is plastic.

Its key aim is to scan a control Kodak slide to adjust color rendering.  The holders are without glass which prevents possible Newton rings but also creates complicated problems when scanning non-standard films, for example, of the Horizon camera. The holders for the 35mm film has bars every 36mm, and you can't fix such film in the wide-film holder. Frankly speaking, I didn't like the way the holders are designed. The Minolta has it better. But you will get used to it. Besides, you can mount several frames in a row, that is why you will have to make this operation less frequent. But it's inconvenient because you place the film, cover it with the frame with lugs and then shift the frame with the film until it gets fixed, and the film can get scratches from the bars it slides along. Fortunately, it values wide films much more. The scanning time hardly depends on the PC connection interface (24x36mm,

4000 dpi, 16bit IEEE 1394 - 117 s, SCSI - 113 s) and it's noticeably greater

compared to the Minolta (6x6 cm, 3200 dpi 16bit; Minolta - 78 s, Microtek

- 377 s). The scanner doesn't support hardware image correction ICE, ROC,

GEM. It's implemented with the LaserSoft's SilverFast software which features

a lot of various settings and a base of settings for many types of negative

films, though far not for all films.

Sometimes software solutions look superior. Scratch removal adjustment

takes a lot of time but you can use different algorithms for different

frame parts. You can create several masks, each of which will process a

given frame section and remove defects of a certain type. In particular,

it can remove horizontal or vertical scratches of a certain type which

is vital for scanning archives which are usually stored in rolls. Such

selectivity can't be delivered by hardware solutions - most of them can't

even process black-and-white films.

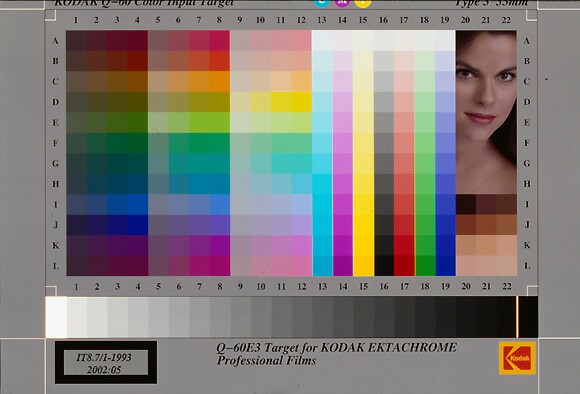

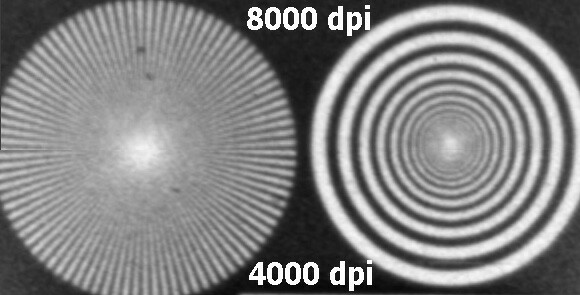

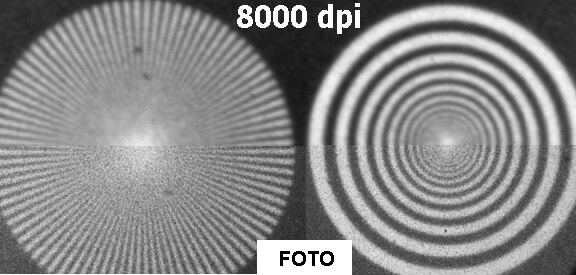

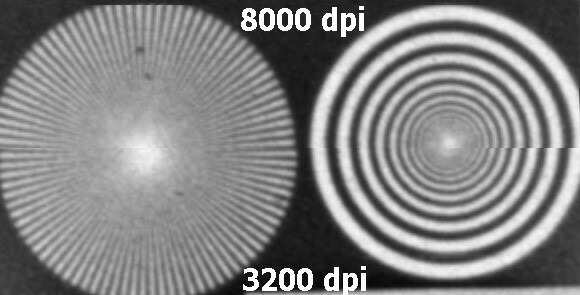

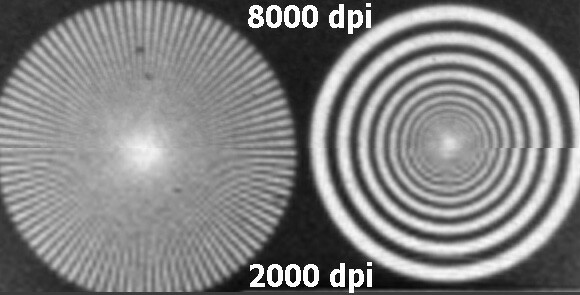

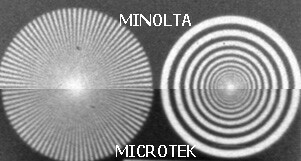

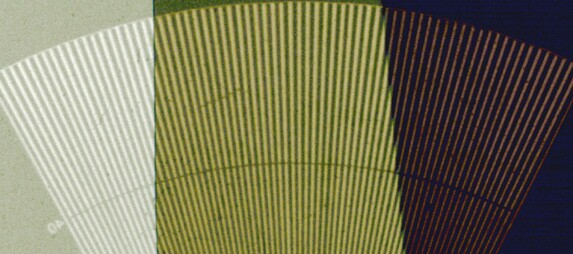

Focusing is only automatic, and sometimes it's difficult to make it work optimal. But when you get an acceptable result for a fragment you can disable it and scan the film further with the focusing obtained. Resolution The maximum optical resolution is 4000 dpi. You can also set 8000, but as you can see it's equivalent to 2x enlargement in a graphic editor. Films usually contain a bit more information. The resolution chart shown was shot on Mikrat 200 film with the Yashica 28-80 lens. Compare the images below resulted from scanning and shooting under a microscope with the Casio QV4000 digital camera.  PHOTO The shot made with the camera is scaled down. Below you can see the central part of the resolution chart (starting from the 5th circle).  The digital camera can get only a small fragment, but the enlargement noticeably exceeds the film potential. It's easier to estimate losses by the radial resolution chart:  You can distinguish 1.4 times more strokes per unit of length, but in such resolution the grain is worse than the lack of tiny details.  The resolution of 3200 dpi completely realizes the scanner's potential, while at 2000 some information gets lost.  If you compare the charts scanned with the MICROTEK ArtixScan 120 tf and Minolta Dimage Scan Multi Pro at the resolution of 4000 dpi, you will see that the images are almost identical.  The scanner perfectly processes high optical density.  Black-and-white negative. The first zone is the negative, the second zone is covered with the filter of the one-order reduction, the third zone is covered with two filters of the total two-order reduction. That's all about the scanner. Now we turn to the achievements of film and digital cameras. CompetitionOne day we bought the Kodak ProFoto 100 film for 35mm cameras and Fujicolor REALA ISO 100 for medium-format ones and arranged a competition for the brightest models in our collection of photo cameras. Participants: In the heavy-weight class we have Bessa Voigtlander and Mamiya C33 with the frame formats of 6x9 and 6x6 respectively. In the mid-range class we have both amateur-level and professional cameras: distance-measuring Welta and Zorki-6, reflex Canon EOS 50 and Canon Prima ZOOM (a classical point-and-shoot camera) . Among the digital cameras we have Canon G2 and Canon EOS D60. The analysis shows that the upper rational resolution for the Bessa Voigtlander is 1200 dpi, the further resolution increase doesn't reveal new details but even makes the image blurrier. At the frame format of 6x9 cm we got a frame of 2614x4027 pixels, 10.5 Mp. The camera can compete against modern professional digital cameras, but you can use any flatbed scanner of $150 to scan its shots, that is why it was taken out of the competition.  75 years ago Voigtlander released a simple folding camera for amateurs - Bessa. Thin pressed metal, decorative leather cover. Voigtar Voigtlander-Braunschweig lens 1:6.3 F=10.5 cm, anastigmat. A-C-Gauthier shutter (ACG), exposures: T, B, 1/125, 1/100, 1/50, 1/25, apertures: f/6,3/8/11/16/22. Tèï 120 film. Frame size 6x9 and 6x4.5 cm.

Now you can see the same picture taken with different cameras. All the miniatures are 5% of the original, and the fragments are 100%. The gallery also includes a shot taken with the Canon D60 from the negative made with the Canon EOS 50. The film has enough potential to make such version looking acceptable, but the above scanner delivers better image with the pixel resolution being the same. It's quite another matter that the scanning resolution is limited and independent of the frame size, in retake you can get a 6Mp image of an indefinitely small fragment.

100% fragments

The photos made with the digital cameras look more finished. The images after scanning at 4000 dpi want further processing in a graphical editor. They contain more information than a file recorded with a digital camera, but the most part of the information refers to the film structure rather than to the objects. All the cameras, except the Canon Prima ZOOM, allows for framing, and their resulting images look comparable to the 6Mp digital camera at 2x enlargement. So, you can get the same results on a postcard with all the cameras: by changing the lens focal length 2x and framing in case of the point-&-shoot camera, and at the expense of framing at printing in case of the older cameras. Probably, the Canon doesn't look so good because it had the Konica VX 100 film, though it's doubtful. Note that the lenses with the constant focal length have a significantly greater aperture: 1:2 of Welta against 1:5.6 of Canon Prima ZOOM. It turned out that the auto system doesn't have a large effect when you shoot landscapes; the exposure wasn't set properly on the old cameras because the shutter speed changes with time, but modern films can easily adjust it within 2 steps. The experience shows that at this level of precision you can estimate illumination by eye. The shot taken with the Zorki was scanned in the increased sharpness mode. It hardly differs from the shot taken with the EOS 50 with the 50mm lens, and I show this picture so that you can see that in such a high resolution the increased sharpness accentuates the grain rather than the object's outline, and far not everyone would like this mode. At a lower resolution the grain isn't so noticeable, which makes this mode more optimal. The G2 has the best fragment quality, but it also has the smallest shot, that is why it yields both to the Mamiya C33 and to many other 35mm cameras. But taking into account that the shot has to be smoothed and scaled down for the equal quality, the film's advantage is not double. Besides, the cameras with the fixed focal length score better results, that is why the 3x-zoom lens will let this camera go on a par in some cases. The winner is the Mamiya C33, as it's difficult to compete with 53Mp shots even accounting for the need for further smoothing. The MICROTEK ArtixScan 120 tf scanner helped a lot here as it let this camera fully realize its potential even in this digital era. Write a comment below. No registration needed!

|

Platform · Video · Multimedia · Mobile · Other || About us & Privacy policy · Twitter · Facebook Copyright © Byrds Research & Publishing, Ltd., 1997–2011. All rights reserved. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||