|

||

|

||

| ||

We have touched upon the issue of measuring memory latency on platforms with Intel Pentium 4 series processors many times. There is nothing surprising about it – the problem is real, it's very difficult to measure memory latency with these processors due to considerable tricks manufacturers resort to, especially in the latest Prescott/Nocona cores, in order to hide these latencies – that is memory access delays. By these tricks we mean the hardware prefetch of data from memory as such in the first place (its implementation details are unknown) as well as its most important feature – prefetching two cache lines from memory into L2 cache of the processor. The latest official method, described in the article "DDR2 – the Coming Replacement of DDR. Theoretical Principles and the First Results of Low-Level Tests", was released approximately six months ago and has been successfully used in our testlab for all this time. There is nothing wrong about it now – it can still exist as one of the possible methods for evaluating memory latency in real conditions. Let's give a recap of this method.

So, the main problem of measuring memory latency on the platform under review is conditioned by the two circumstances mentioned above: Hardware Prefetch mechanism in the processor and prefetching two neighbouring 64-byte lines from memory into the processor cache.

The picture above illustrates the heart of the problem. It shows how the latency of reading two 32-bit elements from memory depends on the distance between these elements (in bytes). This test is used by the RMMA benchmark package as an internal method for measuring the effective L2 Cache line size, which in our case amounts to 128 bytes. Prefetching two 64 byte lines can be seen in all cases – latencies for forward and backward, pseudo-random and random walks grow just a little when the distance between elements exceeds 64 bytes. The further growth of latencies (from 128 bytes and higher) progresses in a totally unobvious way. The reason for this phenomenon is different (the first in the list): enabled hardware prefetch algorithm. The picture is clear and predictable only at random walk. So, the most correct latency values should have been expected in this case alone, but there is another shag to it. This time it's a small D-TLB size. The fact is that the random memory walk depletes it rather fast. The load of memory pages in this case is also random, thus, D-TLB can effectively cache the number of pages that does not exceed its own size. So we get only 128 (buffer size) x 4 (page size) = 512 MB of memory. And this test uses a relatively large 16 MB block... It's not difficult to calculate that the percentage of D-TLB misses in this case will be (16384 – 512) / 16384 = 96.88%, which costs this family of processors very dearly. Note that this limitation does not extend to linear walk modes, where the D-TLB entries are replaced consecutively and smoothly. There is also no limitation at pseudo-random walk – that's the purpose it was developed for. This method loads pages from memory in the forward and consecutive order, and walks page elements in a random order. Taking into account the above-stated theoretical grounds, we decided to use the following parameters for the memory latency test in our first official method.

This mode yields approximately the following result.

Pseudo-random and random walk curves stay almost on the same level, i.e. Hardware Prefetch efficiency does not change at increased unloading of Bus Interface Unit (BIU) of the processor. Unlike forward and backward memory walk curves, where the bus unloading obviously raises Hardware Prefetch efficiency. At one time, the analysis of this data brought up a conclusion that measuring memory latency using this method (pseudo-random walk data) could be considered quite adequate.

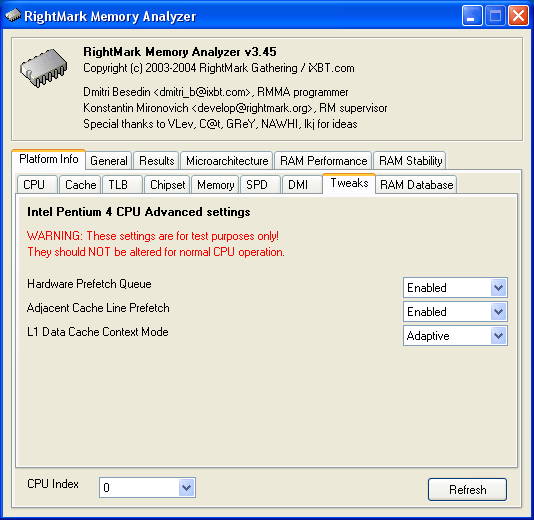

So, everything seems all right – what else can you think of to cheat the cunning hardware prefetch, and why? Let's start with "what". It looks like you cannot possibly cheat the hardware prefetch algorithm, but you can always... disable hardware prefetch! This feature is available in all Pentium 4 and Xeon processors, but the corresponding BIOS settings can be accessed only for the latter as a rule. That's how it all started, we decided to carry out a little research and find out whether they influence test results and how – it turned out that they had a great effect! In this connection, they were added to a separate tabbed page in the new RMMA 3.45 (latterly, we like to play with specific settings of Pentium 4 processors). That's how this tabbed page looks.

Note: these settings are added solely for testing purposes, and the benchmark will warn you about it. It's recommended not to change them to preserve normal operation of the entire system on the whole and of CPU in particular. Let's provide a short description for each setting.

So, the main point here: from now on we have an option to disable both features of the hardware prefetch mechanism: the algorithm proper as well as the adjacent cache line prefetch (which can be used independently of Hardware Prefetch). Here are the directions how to measure memory latency using Method 2.

It's high time to see the settings in action. At first, run the test – Microarchitecture -> D-Cache Arrival, L2 D-Cache Line Size Determination preset.

The result is an "almost perfect" picture for adjacent cache line prefetch (we haven't disabled it, remember? That's the idea). Let's go on: Microarchitecture -> D-Cache Latency test, Minimal RAM Latency, 16MB Block, L2 Cache Line preset.

The result is very interesting. The random walk curve remains almost unchanged – both quantitatively and qualitatively. Thus, in case of random memory access, Hardware Prefetch is practically idle even if it's enabled. But what about the pseudo-random walk? The corresponding curve looks as before qualitatively, but quantitatively... it went up approximately by 30 ns! Conclusion? When enabled, Hardware Prefetch operates with some efficiency even at pseudo-random walk! Prefetching seems to operate on the level of whole memory pages. It can be avoided in two ways only: either use random walk (but keep in mind the imposed restrictions on D-TLB size), or disable prefetch completely. Whether it's necessary is another question. So we've approached the other question asked – "why". Which results should be taken more seriously – with hardware prefetch or without it? In other words, should we disable Hardware Prefetch during testing? The answer to this question is very simple: it all depends on what we want to measure. If we need to evaluate real latencies when a processor reads data from memory in one of the test-simulated situations – forward, backward, random or pseudo-random memory block walk (the first two of them correspond to encoding video or some other data stream processing, and the last two – for example, to searching a database), then we should choose the first option. It's this option that will reflect the reality, that is the standard CPU operating mode: Hardware Prefetch is enabled, and data from memory is read by 128 byte sectors forming two CPU cache lines. To sum it all up, the first method allows to evaluate the real latency of memory system on the whole, that is including functional units of a processor, which are responsible for data exchange with memory. But if we need to evaluate some characteristic, which is closer to real latencies for accessing an array of storage cells, we would need the second method. Because it covers a narrower part of memory system – the carrier (module chips) as well as the chipset. Thus, it allows to evaluate memory access latencies irrespective of processor interface features that are responsible for memory exchange (BIU).

And finally, you can use a combined method: measuring the latency for pseudo-random access to 16 MB block at 128 byte strides at first with hardware prefetch, and then without it. And use the obtained range of values as an evaluation of possible real memory access latencies in various situations.

Write a comment below. No registration needed!

|

Platform · Video · Multimedia · Mobile · Other || About us & Privacy policy · Twitter · Facebook Copyright © Byrds Research & Publishing, Ltd., 1997–2011. All rights reserved. |